Andrew Hallam

01.07.2020

Value Investors: Don’t Get Fooled By The Norse God, Loki

_

About 200 years ago, the Norse god, Oden, put the mischievous god, Loki in charge of the stock market. “Look, you little twerp,” he said. “Over 30-year durations, make sure the stock market earns between 7 percent and 11 percent per year. If it doesn’t, you’ll burn.”

Loki didn’t want to become a char-broiled steak, so he did what he was told. True to his nature, however, he didn’t want investors to earn good returns. He preferred to mess with their heads instead. At times, he pushed stocks higher than Oden asked. Other times, he forced stocks to crash. This suckered plenty of people to buy high and sell low.

But he added a little twist, just to be a jerk. He ensured that cheap, under-rated stocks beat popular stocks. He knew a few smart people would catch on to this plan. But he planned a few tricks to trip them up as well.

Benjamin Graham, Warren Buffett’s professor at Colombia University, learned a lot from the stock market crash of 1929. He was one of the first to question the wisdom of buying high-priced popular stocks. His teachings were Socratic. In other words, he asked questions from which he guided students and readers. In the introduction to his 1940 book, Security Analysis (second edition), Graham asked whether Wall Street could, at times, overly favor large, popular stocks while ignoring smaller, cheaper companies.

He concluded that investors should buy cheap, unpopular shares. As a result, many of his former students grew rich and somewhat famous. Warren Buffett outlined their stories in his essay, “The Superinvestors of Graham and Doddsville.”

Years later, two professors at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, Eugene Fama and Kenneth French, discovered something Loki hid. Investors didn’t need individual stock-picking skills. Instead, they could buy indexes of under-appreciated stocks, known as value stocks, and beat the returns of the overall market. Their emphasis on cheap stocks was how Graham’s former students all performed well, despite using different stock-picking methods. Fama and French found that over long time periods, underdogs win. The firm, Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA) built index funds on this premise.

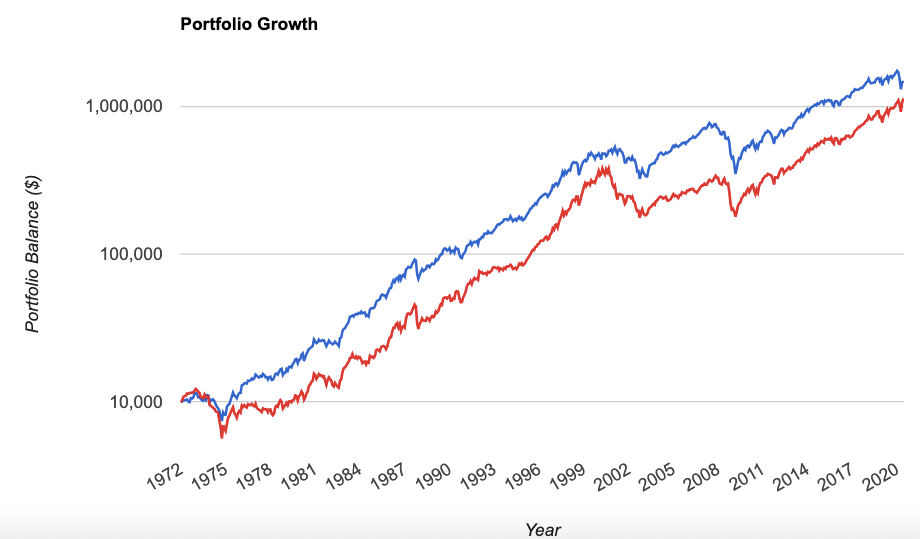

For example, if $10,000 were invested in an index of large U.S. value stocks (businesses with low price-to-earnings and low price-to-book values) it would have grown to $1.47 million between January 1972 and May 31, 2020. By comparison, if $10,000 were invested in popular growth stocks (businesses with high earnings growth and higher price-to-earnings ratios) it would have grown to $1.12 million.

Large-Cap Value Stocks

Large-Cap Growth Stocks

January 1972-May 31, 2020

Source: portfoliovisualizer.com

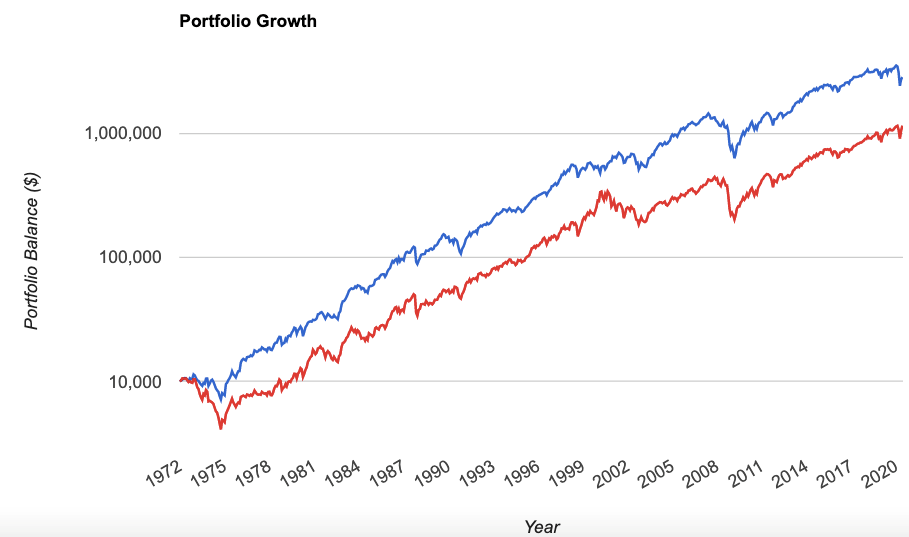

This became known as the “value-factor premium.” It’s even more evident with mid-sized stocks. Between January 1972 and May 31, 2020, a $10,000 investment in U.S. mid-cap value stocks would have grown to $2.8 million. In contrast, the same $10,000 would have grown to $1.14 million in popular mid-sized growth stocks.

Mid-Cap Value Stocks

Mid-Cap Growth Stocks

January 1972-May 31, 2020

Source: portfoliovisualizer.com

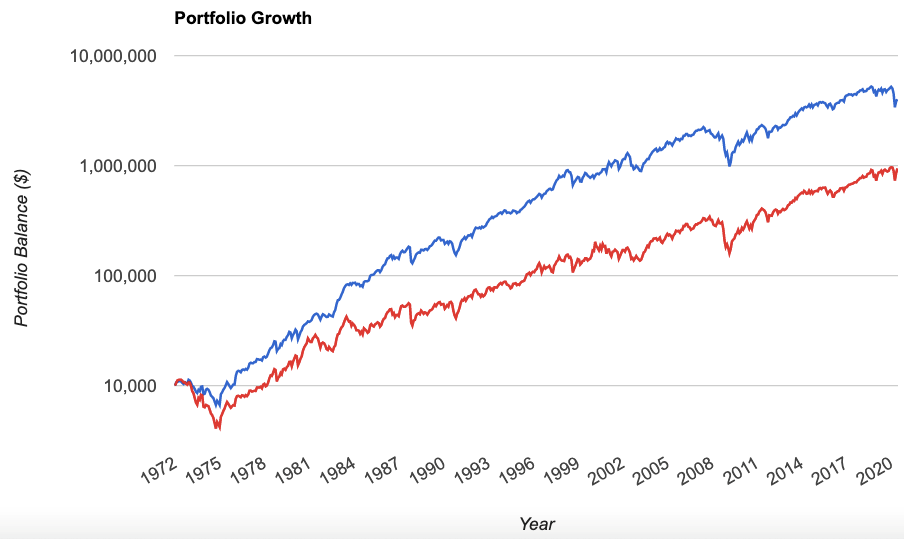

With smaller stocks, there’s even a bigger difference. Between January 1972 and May 31, 2020, a $10,000 investment in small-cap U.S. value stocks would have grown to more than $4 million. In contrast, the same investment in small-cap U.S. growth stocks would have grown to about $943,000.

Small-Cap Value Stocks

Small-Cap Growth Stocks

January 1972-May 31, 2020

Source: portfoliovisualizer.com

Fama and French also noticed that small stocks beat large stocks. Academics have since questioned this notion, as I explained in my column, Three Questions That Bruise The Small-Cap Performance Promise. But robust, peer-reviewed evidence still supports the value-factor premium. In other words, cheap underrated stocks beat popular growth stocks.

But here’s when Loki giggles. Occasionally–sometimes for several years– he makes high-growth stocks win. That happened in the late 1950s, with the so-called “tronics” stocks. It happened in the early 1970s, with some of the popular “Nifty Fifty” stocks. It also happened during the dotcom boom in the late 1990s. In each case investors said, “Price no longer matters. Popular stocks will keep winning.” But as history revealed, Loki always laughed last.

Notice the first two charts above. Focus on the late 1990s. You’ll see the red lines (representing growth stocks) began to rise far more steeply than the blue lines (representing value stocks). In some ways, this repeated what happened in the late 1920s, the late 1950s and the early 1970s. Investors fell in love with growth. They ignored price…and Loki rubbed his hands as investors fell into his trap.

Value stocks performed well over the past 13 years. But growth stocks did better. As a result, research Affiliates’ Rob Arnott, Campbell Harvey, Vitali Kalesnik and Juhani Linnainmaa noted that the gap between the price-to-earnings ratios of growth stocks and value stocks has never been wider than it is right now. It’s even wider today than it was in the late 1990s.

The gap between value and growth isn’t just seen in the United States. That means value stocks are poised to beat growth on a global level. It might be this year. It might be next year. Nobody knows for sure. But at some point, value stocks should win again.

If you’re looking for a global value stock ETF, you might select the iShares MSCI World Value Factor ETF (IWVL). It trades on the London stock exchange, and it charges expenses of 0.30 percent per year.

Investors might also be interested in the iShares Edge MSCI USA Value Factor (IUVD) of U.S. stocks. It charges 0.20 percent per year. For those solely seeking low-cost European stocks, the iShares MSCI Europe Value Factor ETF (IEDL) might fit the bill. It charges an expense ratio of 0.25 percent per year.

Unfortunately, most investors wouldn’t want one of these ETFs. Instead, they would look to the funds with the best recent track records.

Meanwhile, Loki floats above and rubs his hands in glee. “Silly humans,” he might say.

Andrew Hallam is a Digital Nomad. He’s the author of the bestseller, Millionaire Teacher and Millionaire Expat: How To Build Wealth Living Overseas

Swissquote Bank Europe S.A. accepts no responsibility for the content of this report and makes no warranty as to its accuracy of completeness. This report is not intended to be financial advice, or a recommendation for any investment or investment strategy. The information is prepared for general information only, and as such, the specific needs, investment objectives or financial situation of any particular user have not been taken into consideration. Opinions expressed are those of the author, not Swissquote Bank Europe and Swissquote Bank Europe accepts no liability for any loss caused by the use of this information. This report contains information produced by a third party that has been remunerated by Swissquote Bank Europe.

Please note the value of investments can go down as well as up, and you may not get back all the money that you invest. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.